1. TRASH

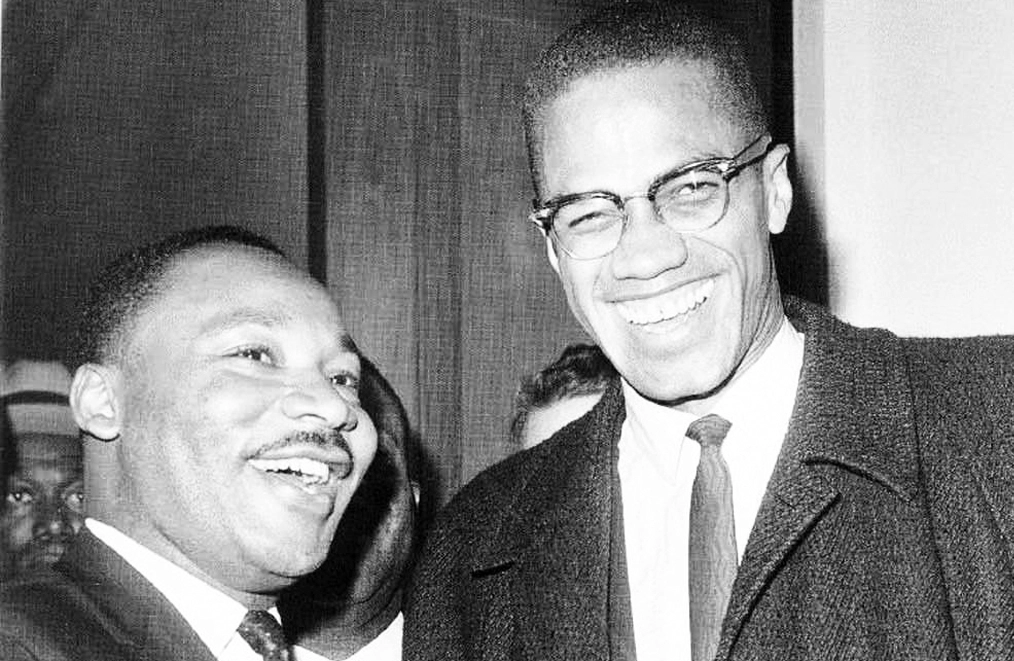

In the pantheon of great American films, I put Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing right at the very top of the list. I’ve talked about why in detail before. It is a towering document of both the humanity and rage of the collective black experience in America. It is about film about the tapestry of views, the aching pain within damaged souls, and the troubling duality of what it means to be young, black, and aware of the world around them. It’s the duality of Radio Raheem’s “LOVE” and “HATE,” writ large. It’s duality of instinct in the better angels of one’s nature and necessary disgust with needless death. It’s a duality expressed in the notion that we live in a world where white America still lauds Martin Luther King (while erasing the complexity of his message) and still demonizes Malcolm X (while erasing the humanity of his message). It posits that to be black, means to inherently carry both figures as instincts inside of the heart. And to feel the constant struggle between them as one goes about navigating life from breath to (hopeful next) breath. And while this “duality of the soul” is something recognized as being true for every human being on earth, we still don’t “allow” it to be true in meaningful ways for black people. We condemn them for not protesting peacefully. And when they do, we then condemn them for that anyway. We condemn them for throwing trash cans. Because the point of any mixed message is control, for we want to be able to tell Black America that they are wrong no matter what they do.

While it is impossible to say any given interpretation is ever “correct” when it comes to a film, if you will please allow me the one moment where I express pride for something I wrote, for Spike Lee said of that essay: “Heartfelt Shout Out To The HULK. This Is The Best Essay Ever Written That Digs Deep Into What I Attempt To Do And What DO THE RIGHT THING Is Really About. I Thank You. Great Job. YA-DIG? SHO-NUFF.” I say this for two reasons 1. the second that was written I could die happy. I’m not kidding. All of this. ALL OF THIS is the proverbial icing on the cake. And 2. It also doesn’t matter whatsoever. Because the point of the essay was that it was not a product of insight. It was a product of listening. It was a product of getting out of the damn way. Even now, what I’m hopefully trying to put forth in this essay is not a product of some white guy explaining how racism works to people who have far more personal understanding, but just a reflection that same listening. And the willingness to be wrong within this conversation about literally everything I’m putting forth. And to listen whole-heartedly to the response as the conversation continues to evolve. All I know is I can argue for nothing more critical, because the thing that is most disheartening about Do The Right Thing is not only how few white people ever seemed to grasp what it was really after, but also how few Hollywood films seemed to take its lessons and carry them forward.

Then again, what else can we expect from a society where Driving Miss Daisy was nominated for awards in it’s place? Far too many people found Spike Lee’s (and still find) opus of Americana too confrontational and incendiary. They even mistakenly thought it a call to radicalization. So perhaps it’s no accident that Hollywood has since instead bankrolled film after endless film where black characters are either lionized for their christ-like suffering and praised for their dignity through pure “respectability politics.” Perhaps it’s no accident they’ve only seemed green-lit stories that secretly make white people feel better about racism (for example, when white people watch racist movies set in the past, they never identify with the villain, but the do-gooder. So it makes them feel like they’e already transcended something). The point is there’s nothing actually being confronted in the audience these films, just put behind us. To paraphrase what Spike Lee always said of this dynamic, “black people never ask why Mookie threw the trash can.”

It’s just a trash can, it’s just a window, and yet it’s so much more. Because there’s a bigger reflexivity to all this which brings us to the current subject, which is Black Panther and why it exists. To which, I have a fuzzy memory that I’m perhaps romanticizing, but want to share none the less… It was a conversation that took place in film school years and years ago between a young black writing student and a white teacher in the program. This teacher fancied themselves pretty progressive, literate in this history of African-American film and all that. And I guess that’s true in a way, but he was still not so subtly trying to get this student to write indie-style confrontational films about the subject of race, “because that’s what the world needs from young black artists!” Of course, the student was interested in coming at it a whole different way. He just laughed at the teacher and said, “Dude, I want to make the next Spider-man.” The disgusted look of the teacher’s face was incredible. He could only respond in sputtering words, “Why do you want to make that trash?” The student replied in a way I will never forget…

“Because you think it’s trash.”

2. GHOST IN THE MACHINE

Regarding such trash, I remember when a lot of people expressed sadness and regret at the idea that Ryan Coogler was going to do “a Marvel movie.”

I mostly bit my tongue for obvious reasons, but perhaps it was a fair observation in some ways because of the way The Marvel Machine, and studio filmmaking in general, is known to chew up filmmakers and spit them out. And the arc of the way Marvel has made movies has been interesting to say the least, particularly in their relationship with directors and thematic storytelling. In phase one, Marvel was still figuring out their modus operandi, but they were taking chances on fun directors and knew enough to ground their entire empire in fun, charismatic characters. I know people always bemoan “origin stories,” but the truth is they’re really good vehicles for both character arcs and establishing what that character is “really about.” And yes, those phase one movies were shaggier no doubt, but they were also genuine and committed to telling different kinds of stories. I genuinely loved them for that. And still do.

But like any successful goliath, the Marvel Machine became too set and rigid in its new M.O. To the point that they were not so secretly convinced they had effectively “hacked” storytelling and thought it was the only right way to engage their audience. They created a uniformed washed-up grey look for their films. They rounded edges. And things that were possible for characters early on were now verboten. It all got to the point that that they pretty severely damaged relationships with a number of directors and storytellers they didn’t think were falling into line (to be fair, the disney acquisition added problems to this). The result of all this was a weird stretch of films that reflected “perfectly polished” inoffensive entertainment that still really didn’t mean much of anything, really. Genre became mere texture while lessons became mere lip service. Overall plots went into wheel-spinning mode. No one ever faced a real fucking consequence for much of anything. They just didn’t want to stop the fun train. And it’s all part and parcel of the reasons they kept the longer slew of more smart-alec white guys while they avoiding those “un-relatable” stories of characters who were things like, you know, “minorities” or “women.” But eventually they caved to the need to do so, mostly because they exhausted their line-up, and insisted it was always part of the phase 3 plan (insider baseball: it wasn’t. They didn’t think the films would do well and were afraid to hurt their streak, so they put it off as long as possible. Fucking own it, guys). But I’m not really here to chastise, as it hopefully turns out this has been the year of Marvel learning a big lesson for the future.

Not just on the story level, like the way James Gunn made a successful movie that actually pulled back to more an intimate scale about family, all with a strong central metaphor. But more with how Taika Waititi essentially tricked them into building a raucously funny ode to the horrors of colonialism. It is the lesson learning how to trust bold choices when made for purposeful, thematic reasons. Which brings us to Black Panther. The truth is that they didn’t dare put the same kinds of handcuffs they did in the past on Coogler. They trusted him largely because they had to trust him. The optics of doing the alternative were too risky. And that was terrifying to them, but they still gave up control and were prepared to take the loss, never expecting in a million years that this film would be the mega-success they’re seeing now (hopefully Hollywood is finally picking up how their modern audience actually works). With all of these, Marvel has seemed to finally learn a big lesson. And maybe it’s one that many audiences, and maybe that old teacher I mentioned gets to learn too: You can put a truly important film about societal divides into something, no matter what the scale.

Because it turns out that Ryan Coolger finally gave us a film with emotional the same complexity and duality of Do The Right Thing and he just so happened to do it on the largest canvas possible: an accessible studio tent-pole.

I can think of no higher compliment.

3. THE BIG IT

I briefly talked to a young someone who was sympathetic, but didn’t understand the lavish praise that was being heaped on Black Panther. Why? Because it just didn’t work for him! It just wasn’t that good! Sure, he could connect to all the logistical reasons people might connect to it. Sure, he could see how it’s “good” to see black heroes in action. But the effect just wasn’t up on screen for him! Meaning people must just be liking the movie for ulterior X or Y reasons!

*sigh*

Look, I see a certain kind of white movie fan talking a lot like this these days. No, it’s not just because it because they lack certain life experiences that prevent them from having empathy for another’s experience. It’s how that gulf of experience directly interacts with this unfortunate left-brain logic where they see movies like a check-list and thus don’t even understand what makes movies meaningful to people in the long run. And not only is this a failure to understand how a movie can transcend small parts that don’t work, but a failure to recognize when they do the same exact thing with movies that are built for them. To wit, even I can admit that certain beats of Black Panther fall a little flat. That it also has to hit some paint-by-numbers beats in the course of executing a giant Marvel blockbuster. Or how, duh, I too have seen better shot action in X or Y movie. But if there’s anything the popular response to Wonder Woman has taught us, it’s how little those kinds of minimal, surface-level complaints actually matter.

Not next to the heights of what it has to offer.

Not next to the sincerity lying under those same beats. Not next to the innumerable scenes full of life and joy and hilarity. Not next to those cool as hell action beats I’ve never seen before (The spear through the windshield, then stopping the car! The fun hilarity of rhino armor!). Not next to the incalculable value of the aforementioned representation, like the fact that the smartest tech whiz in the world is a young African princess who quotes vines and could probably run laps around Tony Stark. Not next to the range of characters and motives and perspectives rarely seen in any films, let alone within a cast of ten (TEN!) amazing black actors who are getting to headline a major studio superhero film. Not next to the gorgeous and loving expression of African culture and afrofuturism. Not next to the sheer litany of little brilliant details of characterization that make the film sing in every nook and cranny (notice how much Klaue usurps not just Black resources, but Black culture). Not next to the sheer competence of storytelling where my concern for the layers of informational prologues ended up mattering so damn much to the emotional pay-offs. So no, those surface complaints don’t matter much not next to all of that.

Especially because the movie goes deeper than that. Especially because the film nails the soul and meaning within itself, which matters more than anything else. So luckily for us, this is a movie that gets the big “it.”

4. REFLEXIVITY

I don’t care when people talk during the movies.

I really don’t. I grew up in a city. Maybe I just gotten used to it. I don’t know. I’ve just never cared. Besides, few people realize that most of the time people are just talking “with” a movie, it’s not like they’re rambling about their day or something. I honestly have a much bigger problem with bored white teens and people who check their phones, for a shining white light is way more distracting than someone cracking jokes in the spirit of the movie. I mention all this because of another anecdote: At my screening last night, a couple of guys talking were making jokes and at one point they got shushed by someone. And one of them replied in a kind of indignant fashion, “are you really telling me to shut up during Black Panther?” People laughed. I smiled. It felt like this weird zeitgeisty moment of cultural ownership, where a movie was coming out in support of theater camaraderie and its audience. But there was a rather telling moment just a few minutes later when characters on screen were speaking in Korean, and those same two jokesters started going “ohhh ching chong ching chong.”

*sigh*

This also isn’t new. There’s a complicated reflexivity in the relationship between the Black community and the Asian-American community and it has been going on a long time (as well as latino culture, but for now, let’s talk about these two). While the narrative of the black experience in American has largely been talked about in popular culture (if problematically) with regards to slavery, civil rights, and the horrific modern climate of racism, the story of racism against asian culture has been one mostly of ignorance and relative silence. Not just in the ugly history of how they built the railroads, or the inhumanity of Japanese internment. It’s in the way people don’t even see Asian people today, unless to fetishize them or crack jokes. Hell, at the Oscars just two years go, right at the height of the socially conscious of the “oscars so white” era, that very same broadcast they make no less than three tired-as-fucking-hell asian jokes, literally about them being good at math / small dicks / etc. Yes. That happened at the oscars (I”m looking at you Chris Rock and Sasha Baron Cohen). The fact that we keep finding this sort of stuff innocuous is fucking absurd to me. This erasure matters. And yes, I could get into the intensely important discussion of how class economics play into the relationship between these two groups (for instance, most don’t realize Asian americans by far have the highest mean income of any ethnic group in america, and that includes white people), but it all brings us right into the reason I bring all this up in the first place: the crux of reflexivity.

Because it’s at the heart of all this. Reflexivity is about how we look at each other and see each other’s commonalities to build empathy, but also how much we see the differences of what we’ve been through. We have to ask, how much of our experience is our own? How much of it is shared? What do we owe each other? What do we not owe to anyone? why? And of course Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing brilliantly accounts for this too, for the relationship with the Korean store owners that is brought in the climax. Same with the way the film portrays white america, both within Sal’s decency and wrath, his lust and resentment, his pride and shame. And most of all, his need for control. And when looking at such questions from our white experience, there is no possible way to ignore the most startling reality: we’ve held so much power and caused so much damage. And thus, the sense of responsibility must take precedence. To the point where the main job is to empower others, get out of the way, and listen.

But of course that scares the shit out of white people because they don’t understand what that really means. They falsely see it as erasure, when really it is not wanting to give up the comfort of power. You’ll see the far right fringe groups echo the phrase “it’s okay to be white!” which I find a laughable weaponization of something that should be obvious. Of course it’s okay to be white. That’s not the issue. The whole point is we are born however we are born, just as minorities are. It’s all just a question of how we take responsibility for the varying levels of advantages that we are born with. And how take that responsibility and extend outward to the communities all around us who are not as lucky. Nothing could be more true for white america, but it’s just as is true within the reflexivity of minority communities. It is the understanding of both shared and different experiences must be expressed with an open understanding and open ears. And as Do The Right Thing also tells us, it is true even within the black community itself. From Mookie, to the Mayor, to Buggin’ Out – they’re all shades of a collective experience, all instincts within the soul, all shades of the same face, and all in need of each other.

And this has everything to do with the very idea of “Wakanda” itself.

In sad truth, the fictional kingdom of Wakanda largely exists to explain why its hero can be possible, which also feels a bit unfair. But it also posits a radical, brilliant notion: that an Africa untouched by colonialism is not the African as many a European would imagine (one relegated to tribal savagery), but a place of progressive modernity and advancement beyond comprehension. Wakanda’s very existence posits that what actually stopped Africa’s development was the theft of Africa itself. From the theft of resources, to the theft of their bodies, to the theft of their very personhood. And metaphorically, Wakanda reflects the “hidden” heart of black pride, capability, and brilliance – all invisible to white america. It is as apt a metaphor as you can imagine. And just as problematic in other ways, for in that creation, a duality was born: for Wakanda to exist, it must be hidden, it must be secret, it must be safe. In other words, it must be conserved. And there are few things more complex than the notion of conservatism within the black community.

Just as there are few things more complex than African politics. Just are there are few things as complicated as black-on-black violence. Just as there are few thing as compli- okay okay you get the idea. But what makes Coogler’s handling of these complex issues so brilliant is not how he refuses to get lost in the weeds of each issue, and instead takes each of them and ingrains them into a simpler overall dynamic: for at the heart of each of those issues is the basic human push-pull between generosity and conservatism, anger and peace, mitigation and power. And, as a true storyteller does, Coogler takes all that and grounds it right into the main character.

It’s just not the one you think.

5. MIRRORS

I know the exact moment I fell in love with Black Panther.

Early in the film, we see T’Challa visit a spirit realm where his ancestors reside and he speaks to his recently deceased father. It’s set in a beautiful african savanna landscape, with this purple otherworldly sky that glows and radiates. They share a tender moment and a promise. It really is a beautiful scene. But this isn’t the moment I’m talking about. No, the moment came later when Killmonger takes his place as the king and does the same exact thing: but instead of visiting that ancestral landscape, he returns to his small childhood apartment in Oakland, not unlike where many young black americans grew up. The otherworldly purple sky still glows outside, but he’s still within the only concrete wilds his young heart ever knew. And he too is brought back to the moment of the death of his father, and he too gets to talk to the man who was lost. But instantly, Killmonger reverts to the little boy he was back then. The father looks at the young boy with sorrow and love, kindly asking him why no tears for his fallen dad? And we see the young boy steel himself, unable to connect to the endless depth of what he’s really feeling. His father expresses regret and goes on to tell him a beautiful story of the glorious heart of Wakanda and all that he really should have gotten to have in his life… we subtly cut back to Killmonger, now listening as an adult, tears pouring down his eyes.

That was the moment. For a scene so loaded with meaning, it is the pitch-perfect dramatization of the way traumas from childhood drive us, but also catch up with us we age. The loss, the fury, the lack of recognition for his pain strikes Killmonger so deep in his heart, but he never learned how to express it. What’s weird is I had a twitter rant just yesterday about this subject, but Killmonger never stopped putting the iron walls around his younger self. Even as he awakes from this deeply emotional dream beneath the sands, he is not crying but screaming in rage. The outward shell knows only how to express anger, murder, and death. But inside, he’s still the young boy, crying wildly, but still trying to be strong for his father, still looking up into the night sky, wondering when it will be his turn to fly through the sky…

To say that Killmonger is the greatest villain in the marvel oeuvre is a disservice to the elegance of what is on display here. In truth, I think it’s one of the best villains I’ve seen in the last 30 years. This is not just because of Michael B. Jordan’s brilliant performance, but because Coogler takes the age old lesson of “make us believe your villain and understand him” and turns it up to 11. Hell, with slight tweaks, Killmonger could just as easily be the hero of the story. And this kinship is not just because of Ryan Coogler’s obvious overlaps in background (there’s a reason it’s 1992 Oakland and he would be that exact age), but from the sheer love and understanding of the character. The film so clearly empathizes and understands the anger and loss within him. And the realization that Killmonger is the character whose experience he directly relates to, for it is the trauma of the black American experience writ large. He is the character that overwhelming majority of black Americans will relate to as well.

And that’s when you realize the unimaginable thing for a film like this: the titular Black Panther is not actually Ryan Coogler’s hero. But neither is Killmonger. For he may understand and empathize with the motives, but the rage is too far gone. So in the end, you realize there are no heroes in this story, just two instincts within the single human. Like Spike Lee conveyed all those years ago, it is the inner MLK and Malcom X: the dueling expressions of nobility and passion, conservation and sacrifice, the proverbial give and take of the human heart. That’s whole point of seeing two mirror images clash with Black Panther suits. But it’s so far from the lazy idea of the hero fighting “himself” – No it is the exact expression of the duality within Coogler and Black america. Just as there was more Malcolm X in MLK and vice versa then we like to admit in our broad strokes paint job of revisionist history.

And the result is so powerful that I’ve seen a lot of people go around posting the idea “Killmonger was right,” and yeah, sure, he’s right – but that’s also a gross reduction of what it actually means to be “right.” Plenty of people are “right” about whatever they’re justifiably angry over – but that’s without the understanding the deeper complication of what that means to put such justice into action. That’s the rub or righteousness. That’s always the rub. As his father tells T’challa. “It is tough for a good man to be king.” And it is equally tough for a righteous man to be fair. And in that understanding, T’Challa, like Mookie, learns the enormous, costly difficulty of what “doing the right thing” can even mean. Especially considering they live in a mixed-message world where people will them they are wrong no matter what they do.

But therein lies the very transcendence. For it results in a superhero story whose “villain” is the one who actually creates the critical understanding within the superhero, all cresting not into a moment of triumph, but a story that literally ends with a heartfelt mea culpa. An apology. An atonement. My jaw was on the floor. It is a film that took the lore of a popular superhero, saw it for what it was, and reformed it into what it truly needed to say for its time and place. As such, Black Panther unspools with a complexity I have not seen talked about with regards to race since, yes, perhaps Do The Right Thing itself. And it has done so in the shape of a blockbuster tent pole that will be an unparalleled financial success. I want to go back in time and declare: “no professor, it’s not trash.”

It is, in short, a miracle.

But everyone says that about things they don’t realize are obvious. The truth is this movie has been sitting around, waiting to be made for decades. For in a world where the Marvel Machine got caught up telling indulgent stories about smart-alecky white uber-boys in the name of create nakedly-vacant power fantasies about fuck all, Black Panther is about the farthest thing from an indulgence that I can imagine. Instead, Coogler has turned superheroism into a desperate plea to the people of the world who are supposed to be his heroes. It is a plea from the depths of the sea, where Killmonger’s haunting final line still rings in my ears as it draws a straight line from slavery to modern incarceration. It is a plea for the voices of those ghosts to be heard. It is a plea from all the kids of America left behind on basketball courts to have their day in the skies. It is a plea to all the deaf ears of not just the world outside the see beating heart of Black & African pride, but even a plea to black conservatism itself. A plea for them to help bridge the divides of class. For Black Panther is a plea, a pledge, a petition, a poem. And it will not be denied.

For it is what he expects from a better world.

And from us.

❤ HULK

This was amazing. Truly. I have nothing else to offer but that.

I hope you’re teaching classes. Our people need to understand This! I was literally complaining about Marvels lack of Asians. I know I’m not asian, but the vast amount of missed opportunities to introduce an important Asian hero is crazy to me. Additionally, I totally comesiarate about the community agreeing with Killmonger’s way of thinking as though that’s a practical solution. While some of this is chalked up to intellect, or age, this sentiment is strong. I don’t worry about being a black woman, but if I were to have a son, I’d hope he would be more introspective and think globally. Loved this review. I rarely agree with anything in it’s entirety but you have out done yourself! Mad respect Hulk!

Someday I hope I can express openly just how deeply this touched me. This was a powerful movie and this is a powerful telling of it.

Excellent article. I took four teens to this movie, and they came out *pumped.* Particularly great to see the empowerment of women in this film, who basically took care of everything.

FYI, I don’t know if you edit these after posting, but:

“Look, I see a certain kind of white movie fan talking a lot like this these days. No, it’s not just because it because they”

This wrote up is exactly what my less educated mind could not come up with to explain why I felt what I felt for the entirety of the movie. Exceptionally well written..

“Because you think it’s trash.” #NailedIt

I don’t even care whether that’s an accurate recollection of the events as they actually happened, that story’s amazing and it’s told exactly the way it needs to be told. (I didn’t read much past there because I haven’t seen Black Panther yet. I’m a bit behind. Thor: Ragnarok was pretty awesome, though! Next up is Justice League. Sigh.)

we briefly discussed my poor phrasing on Twitter 🙂 I wanted to reiterate how much I agree with your article while also, hopefully, rephrasing in such a way as not to make you spit your beverage of choice after the first sentence.

The issue is really one of expectations. In a solo Marvel film, we’ve been led to expect and introduction and/or evaluation of the title character. Captain America :TFA showed us Steve Rogers because of his moral core, not his status as God’s Own Steroid Freak. Iron Man gave us Tony Stark becoming aware of the harm he was doing to the world as an arms dealer (in some respects, Civil War is a reiteration of this and as an aside, it’s nice that changing one aspect of Tony’s character doesn’t automagically make him suddenly humble, vegan and devoted to soup kitchens and pet shelters- he’s still an ass). Thor 1 & 2 did a fairly poor job of teaching us who Thor was (where Ragnarok actually did it pretty well), even Ant Man…. well, you get the idea.

BP, while a great and extremely important film, doesn’t meet this expectation. I still know relatively little about what makes T’Challa tick. In some ways, as a lifelong fan of the comic, I know less.

The comic-book T’Challa is a genius. He’s who Tony Stark and Reed Richards and Bruce Banner and Dr Strange call in when a problem is beyond even them. The film gave that to Shuri, and I get that. Absolutely. It’s empowering and also fun (Letitia Wright was a real ray of sunshine). But it actively diminishes T’Challa in that it leaves him as a man who owes his powers to a herb, his arsenal to his sister and his authority to an accident of birth. Who is he? Why him? Beyond those three bestowed powers, why is he a hero?

I don’t need to go over all the reasons Black Panther is a great film; you’ve done that. But I did want to explain how it is not necessarily the film we’d expect and express a hope that there’s a solo sequel for T’Challa in which his character and what he brings to the role of Black Panther – since it is a role, even for him – are explored as thoroughly as the white-guy films have done it for their protagonists.

He’s a hero because he knows when to ask for help, when to change his mind, and ultimately what his responsibilities to his kingdom are.

Killmonger’s vision quest to speak with his father was my favorite scene, too. Though I wasn’t entirely sure why at the time. I equated it to the opening of Creed, with the young Adonnis talking with Creed’s widow. Just feels like Coogler has such a handle on those types of moments, where kids are conversing with adults, the power of such a thing.

A comic reviewer friend, Shawn Michael Vogt, asked for my thoughts on your article last night and I still have no words. You said them. All of them. More succinctly and informative and just interestingly than I can. And I’m always saying something about this to someone. But I love this, from the whitewashing and erasure of our history to your truly deep and profound thoughts on what Wakanda really represents to the Lost Tribe (which I actually never thought about how sad that truth is).

Sad truths… A lot of white Americans simply won’t understand this; it’s hidden to them, like the various tyrannical systems that brought us here have hidden our true potential as a people. But a lot more white Americans actually are waking up and do hold a responsibility to speak up because of these conversations, and I love that. Thank you so much for writing this. The only way to make a change is to make a change.

There is a running theory on the relationship between Asians, Blacks and Whites. I am going to butcher this so stick with me and do some research on your own. The general jest as I understand it, is that there is if you a triangle between the races. Clair Jean Kim theorizes what is called Racial Triangulation https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Racial_triangulation.JPG . The X axis goes from Inferior to superior and the Y axis is Foreigner to Insiders. Whites are obviously marked at High Superior and High Insider. Blacks are marked as low inferior but high insider (exampled by Lebron James being accepted in American Culture but also being told to shut up and just dribble). Asians however are slated as inbetween inferior and superior (above blacks) but slated as a Foreigner and not an insider (exampled by this post of the black guys being told to shush at black panther but then making fun of the Koreans). Until i saw this literally drawn out, i never understood some of the feelings I had about how i am viewed by both blacks and whites. I’ll be honest, I have had friends literally tell me (both black and white) that they forget that I am Asian. If another race would have said that to them, they would have probably lost it. I am neither black or white, in most cases in the American society that means I don’t count. I loved the Black Panther. I’ve loved all of the Marvel movies. However, I can’t ignore the fact that there will probably never be a Black Panther or Wonder Woman for Asian Americans. There just wont be. It was a nice change to see a wash of another color on screen, but it would be nice to see the world as more than just black and white.

I witnessed an almost identical scenario in one of my film classes: a black student said that he wanted to make superhero movies, and the white professor scoffed at him and said he should only tell, “real, human stories.” I could practically see the genuine, enthusiastic creative spark in my classmate’s eye dull just a little bit when the professor smacked him down. What you saw was, unfortunately, not an isolated incident.

Black Panther is the kind of comic book story I wanted to read 30 years ago. I spent the movie saying to myself “don’t mess up, don’t mess up” and I wasn’t sure until the end whether they would or not. They didn’t mess up. I just wish I were more excited and less relieved, but better late than never.

I don’t know much about US race relations (am in a different country) so I will have to think about that part. Thank you for the context.

Following the… I guess you can call it blow up on Twitter following your initial Do the Right Thing / Black Panther tweet, I, like many others, was a bit astounded by the comparison. Fearful that I was maybe overreacting, I refrained from commenting and tried to let the dust settle. Now it’s been a couple of weeks, and I’ve read the piece a couple of times, and I have to say that while I now better understand where you’re coming from I still disagree.

Like you, I really enjoyed the film. I’ll want to watch it again to make sure, but right now it feels like its far and away the best entry to date in the Marvel universe. There’s a lot of reasons for this–the look (finally, genuinely interesting costumes and colors), the pacing, the willingness to indulge in genre pastiche, the excitement of seeing big-budget fleshed-out afro-futurism on screen for the first time–but the best aspect, as you noted, is Michael B. Jordan’s portrayal of Killmonger. Having a charming, morally and politically persuasive, sexy (you know it matters) heavy does a lot to complicate the central conflict and makes the final battle, usually the weakest part of these movies, feel genuinely compelling. So far I think we are in agreement. Where we disagree is in interpretation.

(I assume) borrowing from the quotes that conclude Do the Right Thing (DTRT), you read the central conflict of the movie through the praxological differences between Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. In the context of DTRT, I think this is astute. In that film, Mooky is dedicated to justice, but is conflicted about how he wants to pursue it. T’Challa, however, has different goals. The plot of Black Panther is determined by two conflicting desires. On the one hand, there is T’Challa’s desire to be a good king. He has to navigate the conflicting wants of the Wakandans, some of whom (represented by Okoye) want to maintain a strong and separate Wakanda, and others (represented by Nakia) want to open Wakanda’s resources up to the world at large. Nativism vs. cosmopolitan liberalism. The other central desire in the film is Killmonger’s somewhat muddled desire for violent, global justice, politically a radical perspective. Charitably, I could see similarities between Killmonger and Malcolm X, who were both interested in blackness as a basis for international solidarity against white supremacy, as well in black self-defense. Martin Luther King, however, is nowhere to be found.

You allude to the historical erasure of MLK’s radical qualities, but I don’t see those same radical qualities in the film itself. MLK wasn’t merely interested in charity and foundations for black people; like Mooky, Malcolm, and Killmonger he was dedicated to racial justice. Unlike T’Challa, he staunchly opposed and threatened the American state (it would be hard to imagine T’Challa receiving MLK’s Suicide Letter from the FBI), condemning it to the point where he had lost any sort of popularity by the end of his life. T’Challa’s main goal, as I alluded earlier, is to be a good king. That requires the maintenance of a throne. T’Challa doesn’t want political change at all, he wants administrative change. By the end of the movie Wakanda is still a super power, it’s still a patriarchy, it’s still undemocratic, and Killmonger is dead. Now, sure, Radio Rakeem was dead by the end of DTRK, but Mooky had also lost his job, and Sal’s wasn’t open for business.

Your article isn’t just a defense of the original comparison, but a defense of the notion of pop film as serious film. I agree with you that the guy in your film class shouldn’t be allowed to make superhero movies, and more than that, I agree that superhero movies can be just as good or interesting as a “serious” movie. However, I do draw a line, and that’s w/r/t method of interpretation. Correct me if this is inaccurate or ungenerous, but it seems to me that this essay is an attempt at a sort of critical hermeneutics, reading past the surface to get at the themes and metaphor that lies within the text of the work. Apart from a passing mention in the third section of the essay, you totally neglect the way the movie situates itself in the afrofuturist tradition. I think this is a mistake.

Interpreted as a drama in the vein of Do the Right Thing, Black Panther is an almost anachronistically reactionary film. T’Challa’s task in the final battle is to work alongside the CIA to defend a monarchy and kill Africans who are attempting to instigate a global emancipation through the proliferation of advanced weaponry. If something at all like or analogous to this happened in a typical drama, it would likely lead to harsh condemnation. That would ignore a key aspect of the film, which is that it is utopian. While there are many strains to afrofuturism (Butler, Okorafor, George Clinton, etc. all have remarkably different approaches), the uniting factor is that they imagine a futuristic reality in which black people aren’t just the oppressed class. One of the most exciting aspects of this literature is how it expands the future imaginary, and asks difficult questions about the distribution of power in a world where black people actually possess a lot of it. Black Panther is a comfortable and thrilling addition to this canon.

To conclude, I don’t think that DTRK and Black Panther are all that similar, and I believe that’s a good thing. Thank God that they’re different. There are a lot of black artistic traditions in this country; challenging, contradictory, serious, popular. Instead of picking at them to find how, underneath it all, they have the same politically satisfying message, let’s celebrate the differences and hope for more.

Only movie I keep in mind considering in a cinema had a black hero. Lando Calrissian, play by Billy Dee Williams, did not have any super natural powers, but he runs his own home. Movie, 1980 Star Warssequel, invented as Calrissian as a difficult individual with the purpose of still did the best obsession. And that’s the only reason I develop up meaningful I could be the same.

Big bro Hulk,

Just wanna say that your craft as a critic so poetically mirrors that of narrative for me. And I’m sure that’s intentional. Like the swings of BP that allowed Killmonger’s declarations to ring loud, my jaw definitely hit the floor when you crescendoed, comprehensively, to that line in your 4th (act): “It’s just not the one you think.”

Thanks for beautifully elevating Killmonger much the same way that Ryan did.

The big letdown for me is that the movie has no idea what to do with its African setting.

E.g. the various kingdoms of Africa had many interesting succession rules (https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/hereditary-succession-and-political-instability), but the movie chooses the very English tradition of trial by combat during coronation instead (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen%27s_Champion), only to ignore its own rules and to allow a challenge long after the coronation.

Nobody in the movie except Nakia seems to care about Africa itself, and there is no hint that anyone in the whole history of Wakanda tried to help their neighbors before her. N’Jobu had to go all the way to Oakland in order to realize that there are poor people in this world. And in a very American reaction, he thinks the solution to the violence in the African-American communities is better guns!

It’s a very American film, isn’t it? I tried to find box office for African countries and only saw South Africa listed. It seems to be playing everywhere but Africa. But then it’s a US fantasy of an African utopia rather than a home-grown African story.

Really interesting post. I do have a question for you. You say Wakanda represents an Africa unmolested by European imperialism. Do you think its portrayal of such an African nation staying isolationist is accurate? Or if given enough time and space, would African societies have sought to become colonizers themselves?

Honestly, though it may not be intentional, that question feels like a transparent attempt to excuse European colonialism, by setting it up as “what any people would have done in their place”.

But that’s nonsense. Plenty of other technologically- and militarily-strong societies have existed throughout world history, but other than the Europe of 2-6 centuries ago, the impulse to spread out across that world planting flags in every piece of land they can find doesn’t seem to have often sprung up in those societies. (Japan dabbled a bit at the start of the 20th Century, mostly in response to the Western colonization they’d seen happening all around them, but did not themselves experience. 50 years later, in the aftermath of WWII, they were out of the colony business.)

In the context of Wakanda, though, the question isn’t framed completely. Wakanda represents a vision of Africa unmolested by European colonization, in a world where European colonization is still a thing that exists, and has still happened to much of the rest of Africa. That makes Wakanda’s isolationist worldview a necessary and integral part of its survival, and makes it seem extra impossible to imagine a scenario where they’d instead take an opposite approach of “colonize them before they can colonize us”.

Because unlike the Europeans of old, or even the Japanese of 125 years ago, Wakandans — like all Africans — were acutely aware, right from the beginning, of all the reasons why colonization was so deplorably wrong and morally bankrupt.

Chiming in late here but the point you raise about the evolution of the MCU is interesting. I’ve been doing a fairly random rewatch of a few of the films, and I’m struck by how much heart the Phase 1 films have, leading up to Avengers. I’m looking forward to Infinity War but I’ll be amazed if they top the emotional impact of seeing the team assemble for the first time in New York.

Phase 2, in contrast, feels largely barren. I didn’t love Iron Man 3, and the Dark World was a bit of a nothing. I actually think that Winter Soldier is my favourite Marvel film so far, but that’s it for top-tier films. Looking back at Phase 3 though, I suddenly see them firing again on all cylinders – a really solid Spiderman film, Guardians 2 which I enjoyed far more than Guardians 1, Doctor Strange, a strong origin story, and then the double punch of Ragnarok and Black Panther (two of the best films to date). The only one that didn’t work for me was Civil War.

I also wanted to acknowledge that I had an interesting reaction to Black Panther, at least at first. As a white, middle class English guy, it was really jarring to see the scene with everyone on the boats heading to the waterfall. There was a conflict between the traditional dancing and music, and the hyper-advanced tech. One of those moments where I had to register my own bias/prejudice…

I loved this film, but I think a better story and a much better ending would have seen Black Panther team up with Killmonger instead of with the CIA (an agency not known for its friendliness towards indigenous and global Africans). However, for Tchalla to team up with Killmonger and to export weapons to all oppressed people across the world would require a radically different story. But such a story would never be greenlit by Marvel/Disney.